UMA testing on large molecules

Meta has just released its deep learning potential model, UMA, which is the most general model that supports different kinds of systems, such as isolated molecules, MOFs, and even surface absorption. It’s extremely easy to deploy and use, even on Google Colab.

It’s pretty like the first time I use xTB. Just hit the “enter“ button on my keyboard, large peptide optimization can be finished in 1 miniutes accurately. That’s the “wow-moment”in computational chemisty.

However, before employing UMA in your research project, it should be tested thoroughly. I believe the best practice usage scenarios for UMA are systems with 100-2000 atoms. For systems containing fewer than 100 atoms, density functional theory (DFT) is the best. In contrast, for systems larger than 2000 atoms, traditional force field methods are significantly more efficient.

Test1: Large Conformers Energy

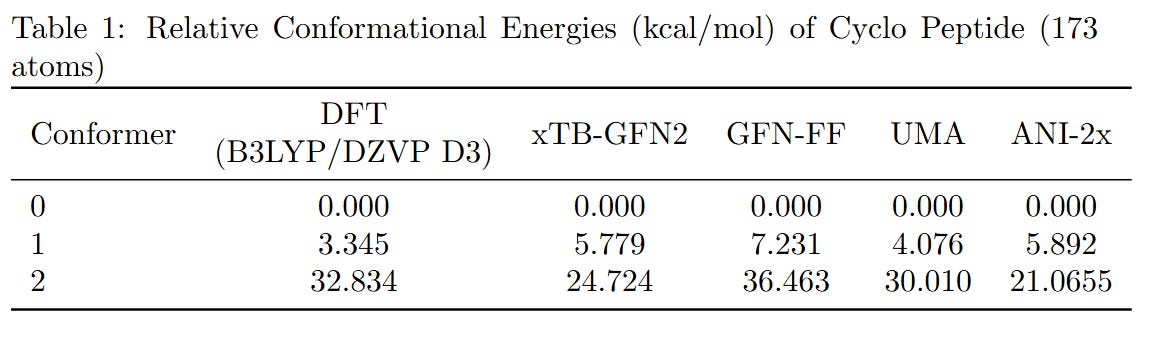

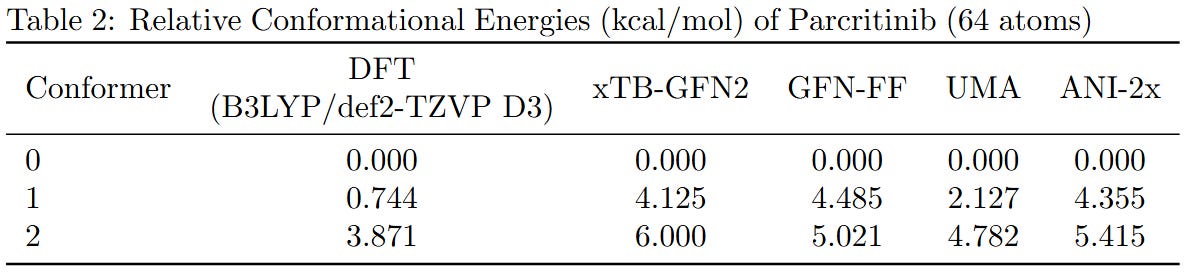

To benchmark the performance of different computational methods on large molecules, we evaluated the relative conformational energies of two representative systems: a cyclopeptide (173 atoms) and parcritinib (64 atoms). The reference energies were computed using density functional theory (DFT) at the B3LYP/def2-TZVP D3 level, and compared with various fast approximations including xTB-GFN2, GFN-FF, UMA, and ANI-2x.

All methods qualitatively capture the relative conformational energy landscape of both systems. Among them, UMA shows the closest quantitative agreement with DFT.

While the AI-based and semi-empirical methods evaluated here were not specifically trained on B3LYP data, we chose the B3LYP functional just because it’s the most voted functional. Due to hardware limitations, the basis set was restricted to fewer than 1500 basis functions. If you can provide higher-level DFT results, we welcome their inclusion for further comparison.

Test2: CNT stretching

In a stress test of the UMA model by running molecular dynamics simulations of carbon nanotube stretching, and compared its performance with that of GFN2-xTB.

Surprisingly, UMA was able to handle chemical bond-breaking events. This is notable because deep learning-based potential models are typically trained on equilibrium structures and rarely include data from highly distorted geometries far from equilibrium. This test suggests that UMA possesses a certain degree of extrapolation capability in predicting the behavior of molecular structures beyond its training domain.

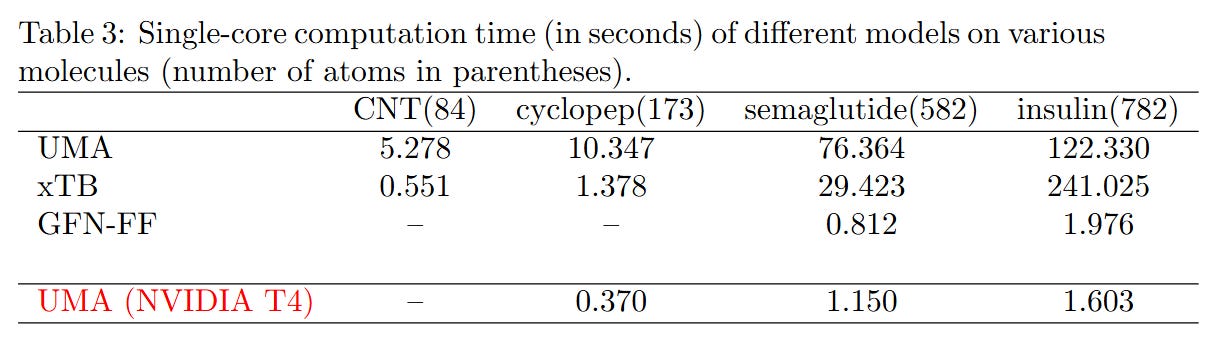

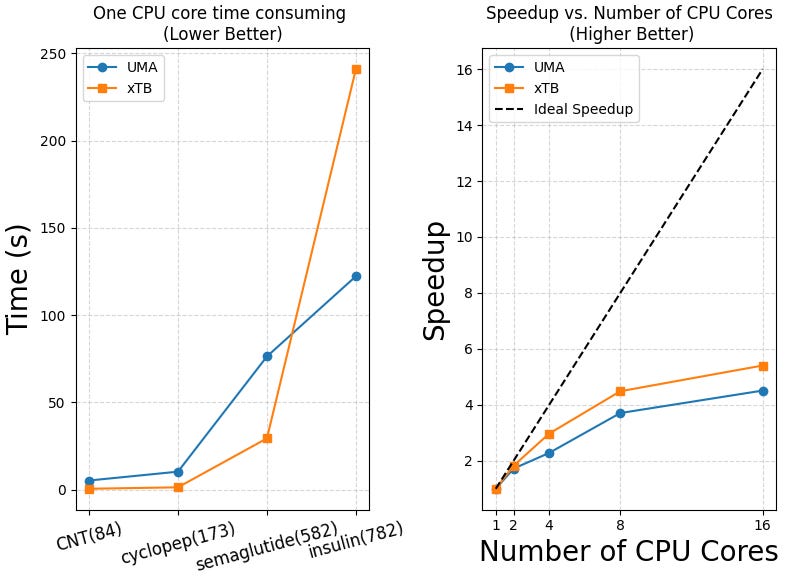

Test3: Computational times

We also evaluated the single-core performance and parallel scalability of the UMA model, with comparisons to xTB and GFN-FF across molecules of varying sizes. As shown in Table 3 and the plots below, UMA demonstrates reasonable efficiency on a single CPU core, although xTB remains faster on smaller systems.

The following code is to guarantee single-core running.

# xTB single CPU

export MKL_NUM_THREADS=1

export OMP_NUM_THREADS=1

# For UMA pytorch

from torch import set_num_threads

set_num_threads(1)

# Timing of UMA

start = timer()

energy = atoms.get_total_energy()/units.Hartree

end = timer()

GFN2-xTB is faster than the UMA model when calculating “smaller molecules” like semaglutide. But for large proteins like insulin, UMA becomes faster. This is because GFN2-xTB still uses self-consistent field (SCF) steps, which become slow for large molecules. UMA and other deep learning models use a simple atom-by-atom approach, which avoids this problem and scales better.

GFN-FF is very fast — it takes only 1.976 seconds to compute insulin on one CPU core. UMA, when run on a NVIDIA T4 GPU, takes 1.603 seconds, but it needs 122.330 seconds on one CPU core.

So, if you don’t have a GPU, we recommend using GFN-FF instead of deep learning models like UMA.

Test data: https://github.com/myzzzz6/AI4Chem

(Please follow our GitHub for more test results)